Look up.

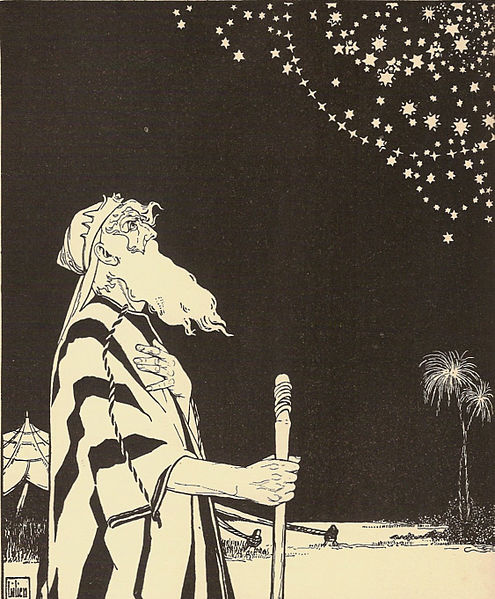

Look up to the sky, said God to Abraham, and count the stars, if you can. That’s how many descendants you will have, how numerous your people will be.

Look up u to the sky, said the last generation of doctors to this one, and count the stars, if you can. That’s how many lives you will save, how many hearts you will touch, how many stories you will change.

What happened to that promise? A recent article by Siddhartha Mukherjee (Emperor of All Maladies, among other works) in the New York Times Magazine, tells a version of the old story about first-year law students looking to the left and right and being told, “One of you will flunk out of school.”

“But in medicine,” writes Mukherjee, “we would soon learn, the danger wasn’t flunking out of school. It was a phenomenon called burnout — being propelled to leave the profession after years, or even decades, of training and practice. ‘Look to your left and look to your right,’ the anatomy instructor might have said one morning. ‘One of you is going to flunk out of your medical life.’”

The name Isaac, Yitzchak in Hebrew, means “laughter.” Laughter. Joy. Happiness. My “Isaac” is the relationship with the people I care for. For most in medicine, it’s become harder and harder to find that part of the dream. We’re not counting stars in the sky anymore. Like Abraham, the dream is about to go up in smoke – tied to the altar like Isaac, to be sacrificed for – what?

Maybe in the name of pinching pennies. I got a letter in the mail 2 weeks ago that almost put me over the edge. It was from an insurer – no, that’s wrong. It was from a third party with a modern sounding name that was hired by the insurer to “review the use of Evaluation and Management codes for all providers as part of ongoing claim review activities.”

According to this third party, I bill “high-level codes” significantly more often than other providers within the same specialty. Specifically, I bill for more “99214” codes, meaning a “moderately complex” office visit, and fewer “99213” or “low complexity” office visits – roughly about 25% more. But lest I feel threatened, “This report . . . is not intended to question a provider’s treatment methods or clinical judgment.”

Well, thank God for that. For a minute I felt like you were questioning my judgment and my treatment methods – because how else am I supposed to understand that letter? I mean, I guess it could be construed as a gentle way of saying, “You’re committing fraud.” That would be much less insulting.

How should I react to such a letter? I could go along, and stop coding so many such visits, at the savings of a grand total of $35 to the insurer every time I do. Given the nine-figure valuation of the insurer, and the fact that I work at a not-for-profit clinic with a margin of a hair’s breadth, that will probably mean that over a year’s time we might not be able to afford one of our staff, while the insurer probably doesn’t even notice.

CMS could cut the documentation requirements, which would inevitably lead all the other insurers to do the same, and make the fee for all visits levels 2-5 the same – meaning if I spend 45 minutes with a patient who has throat cancer, it’s worth the same as a 5 minute visit to treat strep throat. (This is the actual proposed rule for 2019).

I could document even more thoroughly than I already do, check duplicate boxes, and ask questions that are nearly irrelevant but considered grounds for billing more. That would make me even later to my next visits, make my waiting patients angry, and keep me up even later at night finishing charting. I might burn out even sooner. That, according to Mukherjee (in the name of Abraham Verghese), would cost the system anywhere from half a million to a million dollars, and make the rest of the folks I work with even more likely to burn out after me as they pick up the slack.

I could stop trying. As Dr. Sarah Candler of Baylor University put it recently, “The cheapest medicine to practice is no medicine at all.”

Or I could look up. Abraham did, after an angel called out to him, and when he looked up, he saw a ram caught in the thicket, and sacrificed that instead of his son.

When we look up, what will we see? What will we sacrifice instead of sacrificing the thing we love the most – the healing relationship, and ourselves along with it?

The answers to that question are as numerous as the stars in the sky. Some would say government involvement in healthcare should get the knife. Others want to put the EHR to the torch. Others want to offer up all the pharmacy benefit managers on their altar.

My answer is that I think this is a test, and if we think the test has an easy answer – if we think that there is one thing we can remove and solve all our problems – it could hurt us even worse. The whole episode of the binding of Isaac was a test for Abraham – one that some people think he and Isaac failed. Rabbi Hyim Shafner points out that God never speaks to Abraham again after the episode, because Abraham knows very well that God can be questioned and challenged (like he did in the episode of Sodom and Gomorrah), and God expected him to put up a fight rather than passively sacrifice his son.

Abraham’s job wasn’t to be obedient, it was to point out that righteousness trumps obedience, even to God. When Abraham got it right, in the episode of Sodom and Gomorrah, it was by gently, subtly, but persistently challenging God, using different strategies and arguments that all grew out of one idea – do justice.

We, and I mean both healers and patients, need to say no to being sacrificed. We’re not challenging God, just other people who think they know more about our relationship than we do, even though they are two degrees removed (three, if you count the biller in my office) from ever meeting either of us. Not that we’re questioning their judgment or anything…

To do so, we need lots of strategies, not just “get government out of healthcare” or “Medicare for all” or “insurance companies are evil.” For example:

- Draft letters in reply to those insurers and third-party consultants.

- Find out how much they charge for their services (I bet it’s more than the doctor gets paid for theirs!).

- Invite them to see what you do and why helping someone who is in recovery but still has chronic pain and epilepsy, or a seventy-year-old non-English speaker with a long medication list who doesn’t understand how to take them, might be considered “moderately complex,” even to someone with an advanced degree in medical bean-counting.

- Ask for coverage that addresses your real health needs and for compensation that values the time, knowledge and compassion that the healer invests in you.

- Cheerfully refuse to end the visit until you achieve real healing, not the kind of “quality” that satisfies the bean counter.

Look up. Pass this test. Our lives depend on it.