We exchanged a series of sheepish looks as she spoke – Kelly

with me, me with her daughter, her daughter back to her.

“Everything on the left side – first the neck, now the leg,

what’s next? The stomach? The kidney?”

She was wrong, though.

There had been a problem, the right shoulder and neck, with almost the

same symptoms. This went away, then the

identical complaint returned in the other shoulder. I reminded her of this. We all laughed, but it did not ease the

frustration for any of us.

“You’re right. I just

seem to get better from one thing so something else can go wrong.”

I’ve always been captivated by the power of the Exodus

narrative as a parallel for illness. The

Exodus from Egypt is crucial to understanding the Jewish take on the world, but

there is a certain universal appeal. In

the first chapter of Healing People, Not Patients, I recall how my

teacher, Rabbi Larry Heimer, introduced me to an interpretation of the Exodus

by Rabbi Yitz Greenberg that shaped how he, and in turn I, thought about

illness.

The Hebrew for Egypt, Mitzrayim, is the equivalent of

the English, “in dire straits” – stuck in a narrow place from which escape

seems impossible. Greenberg explains

that by being in bondage in “Dire Straits,” the Israelites were in a state that

God never intended human beings to endure.

Slavery is not the natural condition of humanity. The Exodus, in turn, is proof that when

humanity suffers, God hears, and God cares, and God acts.

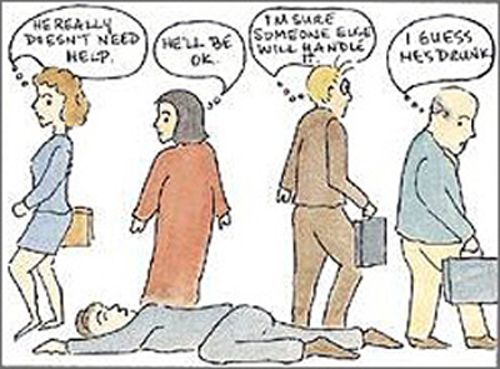

Modern humans stand in for God in acting to relieve each other’s

suffering, including getting each other out of dire straits. The Exodus imagery is supposed to remind us

that healing is possible, and that we are supposed to reach out our arms and

perform some signs and wonders of our own to make it happen. Modern medicine is nothing, if not signs and

wonders galore.

But chronic illness confounds the metaphor. If illness in general is Mitzrayim,

then chronic disease is Pharoah. “I’ll

let you go. On second thought…. Naaaah, changed my mind. Back to work!

Build those pyramids!”

The plagues are powerful medicine, to be sure. “Frogs?

No, not frogs! I give! You can go!”

But no sooner do the Israelites start packing to leave than Pharoah has

another change of his hardened heart.

Kelly can relate; every time we unleash a good plague of muscle relaxers

on one pain, her personal Pharoah comes back with a vengeance in a different

limb.

If you don’t believe Kelly, ask Yuri, ready to return to

work after a long illness, smiling and hopeful in my office one week, only to

return two weeks later because the dizzy spells returned after only three days

on the job.

Or ask a cancer survivor, finally daring to dream and plan

again after 4 ½ years of living scan to scan, who learns of a spot on the

5-year scan that means he is back to square one – only with fewer options.

Ask a person finally ready to cut the cord from medication

after a long journey with depression, only to find herself on the edge of the

precipice once more after the unexpected death of a close relative.

For the person living with chronic illness, there is a

problem with the Exodus narrative. For

all that God promises, that doctors like me who have a hard time remembering

that we are not God promise, and for all that we may deliver on some of

our promises, at the end of the Exodus from one sickness, after the crossing of

the Red Sea that is the ringing of the Mayo Clinic oncology bell, the return to

work, the dancing at a wedding, for all that, the true end result of the Exodus

is to find yourself wandering in the desert for 40 years, relapsing and

remitting, having good days and lousy ones, until someone who is not you

eventually gets to see the promised land of being chronically well.

A couple of nights ago, I participated in a Twitter chat called #medhumchat, discussing the poem “Intensive Care” (and if you like what I write you should participate too; shout out to Colleen Farrel, MD, aka @medhumchat for coming up with this). The poet likens the ICU to a ship adrift at sea, with no instruments – even though the ICU has instruments coming out the wazoo (sadly, both literally and figuratively). It is the kind of ship likely to end up stuck in a narrow place – to be caught in Dire Straits.

I’m not sure how to change this story. The Israelites of the original Exodus

wandered because they were still stuck mentally in their narrow place, never

truly believing they had the agency to be free.

I think we may be making the same mistake – so stuck in the narrow place

of a disease model that envisioning well, especially sustained wellness, is

impossible for us.

How else to explain my shock when I meet a person over 80

who tells me they take no regularly scheduled medications? How else to articulate why I get worried, not

happy, that someone I care for frequently drops from the radar for 2 or 3

years? It couldn’t, God forbid, be that

they are well – there must be something terribly wrong that isn’t

getting my attention, right?

The way to change the story, I think, is to realize there’s

another way to read the analogy. Yes,

the person with the chronic illness is like the Israelites in Mitzrayim

– but so is the healer. Until we healers

learn to stop saying, “No, you’ll need to take that medicine for the rest of

your life, side effects or not,” or to stop telling people to cancel vacations

and grand plans, or to stop acting like the purpose of old age is to stay safe

instead of to live, we are all destined to be stuck here in Dire Straits.

At least they have a good house band….

The next #medhumchat will be at 9 pm on January 16; search the hashtag on Twitter to find out which readings Colleen has chosen and join in! I found it a great antidote to my own Dire Straits – a really good way to read situations differently.

Like this:

Like Loading...