If you could only ask me one question, what would it be?

It sounds like a party game, a conversation starter designed to get people talking at a speed dating event or a team-building exercise. But sadly it’s the way most people’s encounters with their healers go these days. For all practical purposes, there is a “one question per visit rule.” Better make it a good one.

If you’re pretty sure you have strep throat, or you collapsed to the volleyball court knowing with near certainty that you ruptured your Achilles tendon, you’ve got your question all figured out, and you will definitely make it in under the fifteen minute mark. Congratulations on winning the patient Olympics.

But what happens if you have more than one question? Where do you begin? With the burning feet or the panic attacks? The rash on your back or the question of whether the lump in your breast is cancer? Getting your flu shot or getting your power turned back on so your $600 insulin doesn’t spoil in the fridge?

Right around the time I was starting practice, in 2008, Kevin Fiscella and Ronald Epstein, two family medicine faculty at the University of Rochester School of Medicine, addressed this issue in an article, called “So Much to Do, So Little Time: Care for the Socially Disadvantaged and the 15-Minute Visit.” In their opening paragraph, they write, “During 15-minute visits, physicians are expected to form partnerships with patients and families, address complex acute and chronic biomedical and psychosocial problems, provide preventive care, coordinate care with specialists, and ensure informed decision-making that respects patients’ needs and preferences. While this is a challenging task in straightforward visits, it is nearly impossible when caring for socially disadvantaged patients with complex biomedical and psychosocial problems and multiple barriers to care.”

Impossible.

It is the Jewish season of repentance, teshuvah (return or answer), right now. From Rosh Hashanah, which began this past Sunday night, until the end of Yom Kippur next Wednesday after sundown, we are working on righting the wrongs we did last year. It’s complicated, whether you follow Dr. Aaron Lazare’s excellent prescription in his book, On Apology, or Maimonides Laws of Repentance from the 12th century, whose essence echoes throughout Lazare’s work. Jewish repentance involves honest self-critique, humble acknowledgement of guilt, repairing the harm that was done and committing to not repeating the mistake when the same situation arises.

How do you correct a mistake that is impossible to correct? It is a set-up for failure. Which, frankly, is how a lot of family physicians view the whole endeavor of primary care today. Fiscella and Epstein had lots of concrete solutions in mind; 11 years later, we have only seen things get worse.

The day before Rosh Hashanah, my friend Irene Kaplow was teaching the congregation about the verse in Deuteronomy that says, “This instruction . . . is not too baffling for you, nor is it beyond reach (30:11).” Her sermon focused on the interpretation of the words, “This instruction.” Was it speaking of the whole Torah, all 5 books and all of the laws that had piled up in 40 years of Moses instructing the people? Or was there, perhaps, one law that the verse referred to specifically?

Irene went backward in the text for her answer. Deuteronomy 30:1-10 describes what will happen when the people of Israel return to God after being banished among the nations, “once you return to the Lord your God with all your heart and soul.” This is the instruction that is not too baffling, nor beyond reach: the instruction to do teshuvah.

The impossible is not too baffling, nor beyond reach. Somehow, I can fit all of those things into fifteen minutes, address all of the issues, scale all of the barriers, and unravel all of the misunderstandings. It is not beyond reach. Of course! That’s so simple!

Ahhh…. no.

Let’s assume that both Irene and Fiscella and Epstein are correct. Teshuvah is not baffling or beyond reach, and it is impossible to do justice to this mess in fifteen minutes. What now?

The season of teshuvah is actually a good bit longer than the ten days from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur. It begins a month earlier, on the first of the Hebrew month of Elul, and to some degree continues until the seventh day of the holiday of Sukkot, also called Hoshanah Rabbah, nearly three weeks after Rosh Hashanah. The one constant extra observance during that entire period, which is awash in extra observances, is the reading of Psalm 27.

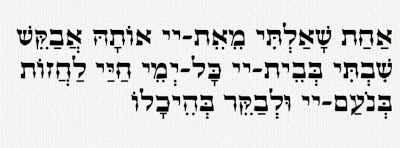

The psalmist, traditionally believed to be King David, had lots of issues to take up with God. He had praises to sing, fervent pleas for God to save him from vengeful King Saul, music to compose for the Temple. But in Psalm 27:4 he cuts to the chase: Achat shaalti me’et Adonai, otah avakesh: Shivti b’veit Adonai kol y’mei chayai. Lachazot b’noam Adonia u’l’vaker b’heichalo. “One thing I ask of Adonai, only that I do seek: to dwell in the house of the Adonai all the days of my life, to gaze upon the pleasantness of Adonai and to visit God’s palace.” (Click here to hear it sung as we do in my synagogue, to a melody by Paul Schoenfeld.)

One thing, from among all of the requests and praises. The most important thing. Achat sha’alti.

And what will happen there, when David gets his request? “God will hide me in God’s shelter on an evil day, hide me in the seclusion of his tent, raise me on a rock.”

When we clear away the noise of the multiple issues competing for our inadequate time, everyone is like King David. There is one overarching thing that they need, and for most people that thing is to feel safe, cared for, and protected from the “evil day,” whether that is a cancer diagnosis, a heart attack, or an abusive spouse.

One problem is that when we ask our opening question, something along the lines of “How can I help you?” this is not what people are sharing. You don’t answer a generic line like that with, “Well, can I dwell in your house forever and have you hide me in your tent on an evil day?” You make small talk, lesser requests, give thanks for previous goods. The first blessing in the formal morning service thanks God for giving the rooster the ability to tell day from night – and let me tell you, having known some roosters who apparently can’t tell day from night, it’s worth giving thanks for. But it’s not the one thing. Except maybe for the rooster.

Holding back from the “big ask” leads to getting bogged down in minutiae. We spend ten minutes on a mild rash, and another ten on checking off the health maintenance boxes, and then at minute twenty of an inadequate fifteen minute visit, the fifteen pound weight loss, the suicide attempt, or the crushing chest pain finally comes up. If we’re lucky. If we’re in enough of a hurry, we are already out the door and it never comes up at all. When fourth-year medical students at the University of Colorado spoke to patients in their university hospital’s emergency room, there was little correlation between their chief complaints and what was really on their mind.[i]

Now I know what my teshuah will be, a teshuvah that is not baffling, or beyond reach. Time is precious; those fifteen minutes need to be treasured. “How can I help you?” isn’t really helping anyone. I’m going the Colorado route – the King David route – when I start my visits:

What is the one thing you are asking today that is most important of all? What is the evil day you are afraid of? What will make you feel sheltered and protected?

The work Fiscella and Epstein laid out still needs to be done. There is a reason Rosh Hashanah comes every year – no matter how hard we try, there will always be more to repent for, including many of the same things we regretted doing this past year. What is “not beyond reach” is making some concrete change – hopefully a change that will lead to meaningful care even in the face of the impossible task before us.

What worries you most – what is your “achat

shaalti?”

[i] http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/medicalschool/centers/BioethicsHumanities/ArtsHumanities/Pages/What-Worries-You-Most.aspx

1 comment so far