Update: Video of the talk is now available online, beginning at 18:18 of the video. Watch the entire clip to see the evening’s other excellent speakers, Rabbi Shira Stern, speaking about “Finding our Resilience by Owning Our Grief,” and Professor James Young, speaking on the process of creating memorials for traumatic events.

Remarks from a “FEDTalk” given at the annual meeting of the Jewish Federation of Greater Pittsburgh, September 5, 2019.

It was the morning of March 17th. 48 hours earlier, a co-worker had alerted me to the horrible terror attack in Christchurch, New Zealand. I had been in a fog ever since. The young Syrian man across from me stared at the floor and told me, “I watched the video online – he wasn’t showing any emotion. He was shooting people like it was a video game.”

Less than five months out from our own communal tragedy, I thought I had begun to heal myself. Christchurch ripped open the wounds – his memories of the catastrophic disintegration of his home country into civil war, and mine of the loss of dear friends, colleagues, and co-workers, and of my illusion of being secure in our wonderful Jewish community.

It was a conversation particular to the Squirrel Hill Health Center. While we are not a “Jewish health center,” SHHC grew out of the Jewish Healthcare Foundation, is a Federation beneficiary, and in many ways is a living legacy to Montefiore Hospital’s tradition of serving all of the underserved communities of Pittsburgh. Those underserved include refugees and immigrants whose language, culture or religion serves as a barrier to care in many places. SHHC was also where our late, beloved friend Richard Gottfried worked until the day before he was killed while davening with his community at New Light.

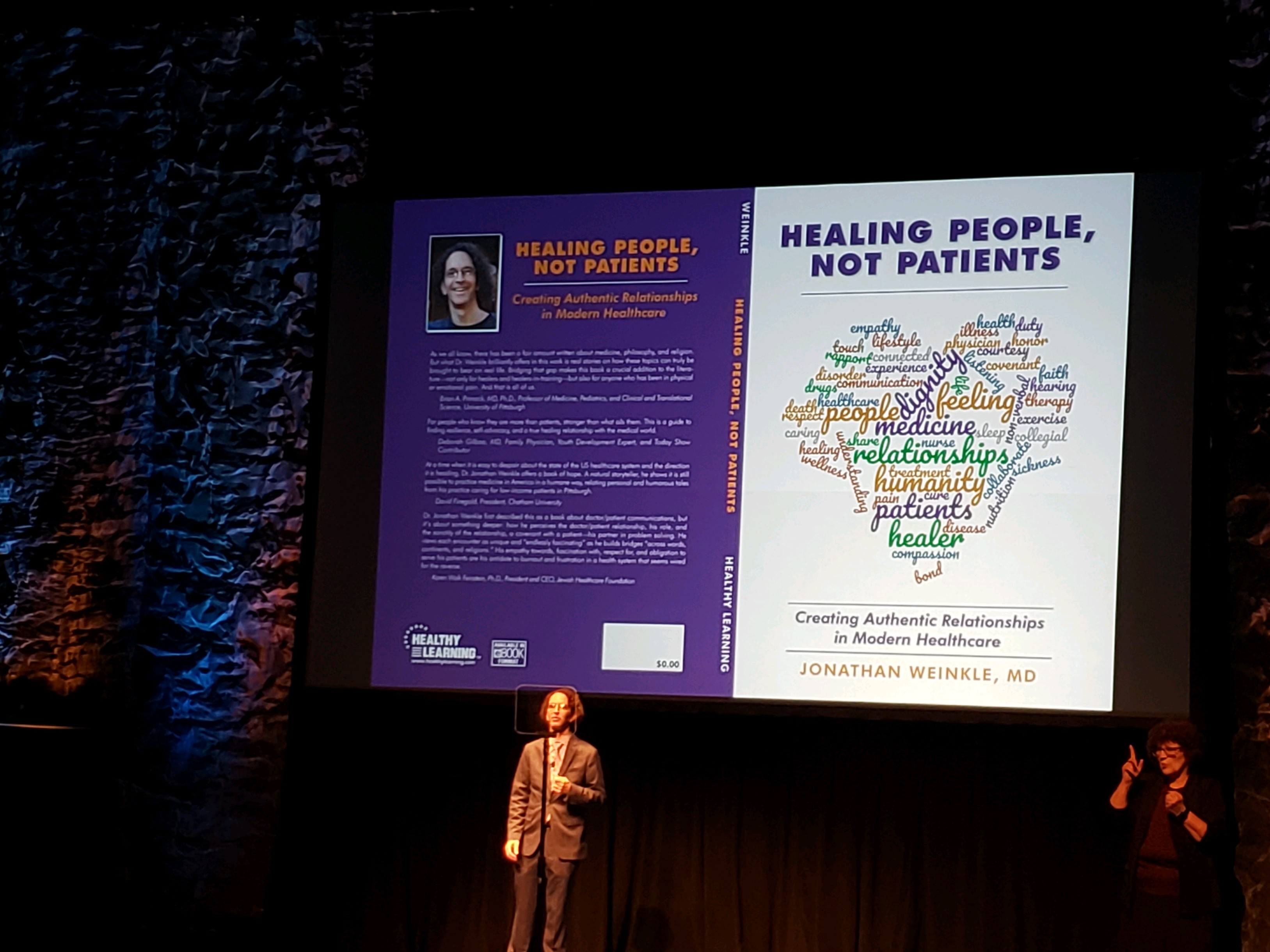

I suppose I’ve known for years that a conversation like this would happen one day. Last fall, just a month before the 18th of Cheshvan upended all our worlds, I reached a major career milestone. My book, Healing People, Not Patients, was finally published thanks to generous support from the Jewish Healthcare Foundation. The premise of the book is simple: people who heal for a living are in a relationship or, as Rabbi Harold Schulweis suggested, a covenant with people seeking healing. Thinking of those seekers first and foremost as people, created in God’s image, demands a completely different approach to healthcare than our current model that often reduces a person’s identity to their diagnosis or even their room number.

The most crucial skill in this covenant is the ability to listen attentively to another person’s story, and to ask them questions out of genuine interest in knowing more. My friend Martin often admonishes me not to ask questions I don’t want to know the answer to. Well, in the aftermath of a tragedy, I don’t want to know the answers. I’m not sure I can handle the answers anymore. Yet those answers are the key to helping the other person heal. What was I supposed to do?

My young Syrian friend is not the only person I care for to have experienced trauma. “Trauma-informed care” is one of the newest buzz-words in healthcare, and especially in mental health. But Dr. Megan Gerber, author of the first textbook on trauma-informed care for primary care docs like me, distills this buzzword into a stark realization: depending on where you are, a history of trauma can be nearly ubiquitous. Consider the SHHC team to be fully informed.

What isn’t ubiquitous is what grows out of that history. Gerber makes the point that people who have been traumatized may be angry and frightened, jumping at a touch or snapping at every perceived verbal micro-aggression, even when the intent of that touch is to soothe or that speech is to counsel. Others bury the trauma almost as soon as it occurs.

Trauma can lead to chronic pain and disability: a back bent into the shape of the lowercase letter “r” which bows even further on the yahrzeit of a lover. At the other end of the spectrum, health workers whose patient dies in mid-shift return to work within minutes. I debriefed after my first experience of a patient’s death in the stairwell of the VA hospital only because the intern supervising me took two minutes to stop and check on me as we ran past each other in opposite directions.

Jewish tradition prescribes a middle path. We find triumph in tragedy, and remember tragedy in moments of triumph. The chevra kadisha, of which our community is blessed to have two that work in cooperation and respect, does a tahara using texts comparing the deceased to a bride, or to the Kohen Gadol. The mashiach is going to be born on Tisha B’Av. The broken glass at a wedding tempers our joy with a memory of Tisha B’Av. And at one point in history, that wedding was likely arranged on the afternoon of Yom Kippur, when the life of each Jewish soul is hanging in the balance.

Saturday, November 3, 2018, the 25th of Cheshvan, when 1500 people crowded the sanctuary at Beth Shalom to mourn and daven together, we ended Kiddush by celebrating the sheva brachot of our Rabbi, Jeremy Markiz, and his wife Elana Neschkes. They married on the 19th of Cheshvan in Los Angeles, and bound by the mitzvoth to rejoice that entire week, even in the wake of unspeakable tragedy. If it is possible to be both broken and restored in the same moment it happened to me as I struggled to sing for the bride, “Kol sasson v’kol simcha, kol chatan v’kol kalah.”

Remember that stark realization about the ubiquity of trauma? Megan Gerber reminds us healers of an even more stark truth: many if not most of us have also been traumatized. We not only need to be broken and restored in the same moment – we need to be broken and restore others in the same moment. Gerber might well paraphrase my friend Martin and say, “Don’t asked questions if you’re not fully prepared to deal with the answers you get.” But we had to be prepared; we had to continue.

The weeks and months that followed the shooting were a pendulum swinging between attending to the pain and suffering of those we had always cared for, and tending to our own wounds. There was Rich’s funeral, the cookie trays and lunches, the Bhutanese community vigil, the outreach from JFCS. Despite their own vulnerabilities, their limited English, their own emotional exhaustion, the seekers were now healing the healers. Their example inspired what I am going to share with you now.

Fans of medical Latin may have heard the term furor therapeuticus, a term the great teachers of medicine often apply to their students who simply cannot stand to leave a problem un-fixed, often to the great detriment of the person with that problem. The golden age of medicine that dawned in the sixties and continues to this day filled many of us with the belief that every disease could be cured, every hurt healed, and even death made optional. We learned to say, “No one needs to be in pain.”

As we become trauma-informed we are learning to say, like Rosey Grier, “It’s all right to cry.” Healers like me who have never really learned properly to shut up now recognize that it’s also all right not to have an answer to the crying. We just need to name it, and be present with it, and share the tears.

Pittsburgh Jews are now trauma-informed whether we like it or not, aware of both the ubiquity of trauma experienced by others, and of our own inability to escape trauma ourselves. It seems preposterous that after 2,000 years we should need to be reminded of the ubiquity of trauma, but individual memory is short. It’s hard for one person to remember what it’s like to be a “stranger” when we are no longer feeling so “strange.” Now, our own immediate experience parallels that of those we support, and of those we try to heal.

Erica Brown, who came to comfort our community on the shloshim, and who will return here later this month for the Fall Forum, takes exception to the five-stage Elisabeth Kubler-Ross paradigm of grief. In her book Happier Endings, Brown contends that there are really only three stages: denial and resignation, which encompass all five of Kubler-Ross’s original stages, and inspiration, in which a new life is formed, absent that which was lost, yet incorporating it into something greater which did not exist before the loss.

The inspiration stage is digging into that parallel experience to help others. Before the shooting I would sometimes ask myself, “What can I learn from my patients who have survived war trauma and are thriving that could help others who are not?” Now I am looking at myself, asking how we might help each other.

Answers are already emerging: by returning support to our Muslim neighbors who rushed to our aid in October. By sending letters to the survivors of the more recent tragedies in Poway, Dayton, Gilroy, El Pason, and now Odessa-Midland. By tapping the resource of our Holocaust survivor community to support our Hillel JUC students, or to partner with SHHC to help Bhutanese refugees process their own tragic losses.

This is variation of the phenomenon known as “concordance:” people build more trust and experience greater healing with a healer who is similar to them in gender or ethnicity. In the Talmud, Nedarim 39b, Rav Aha bar Hanina speaks of a different kind of concordance, necessary for effective healing when visiting a sick person – to be “ben gilo.” One translation is that this means to be of the same astrological sign, but as always, there are other ways to read this.

Gil – age. One of the same age may be more of a comfort that someone too young or old.

Gil – joy. One of the same temperament, who enjoys same things, can provide greater comfort than someone with whom we have nothing in common.

Gil – l’galot, to reveal. If we are vulnerable, broken, and willing to share that vulnerability with the others, we connect in a way that armored stoicism and charmed innocence do not allow.

Glu’im – exposed. The media encampment last fall left us exposed, but in that exposed vulnerability is our strength, our newfound ability to be there for each other.

L’galot – to discover, strength we did not know we had.

Gilinu, we discovered this year what we already knew.

We are surrounded by bnei gileinu, our friends and neighbors with whom we have a special, Pittsburgh concordance.

Bo’u ngaleh, let us show the rest of the city and the world what we have to share with them.